Letters from the Secret D&D Live Show (feat. Sigil)

They had us in the first half, I’m not gonna lie.

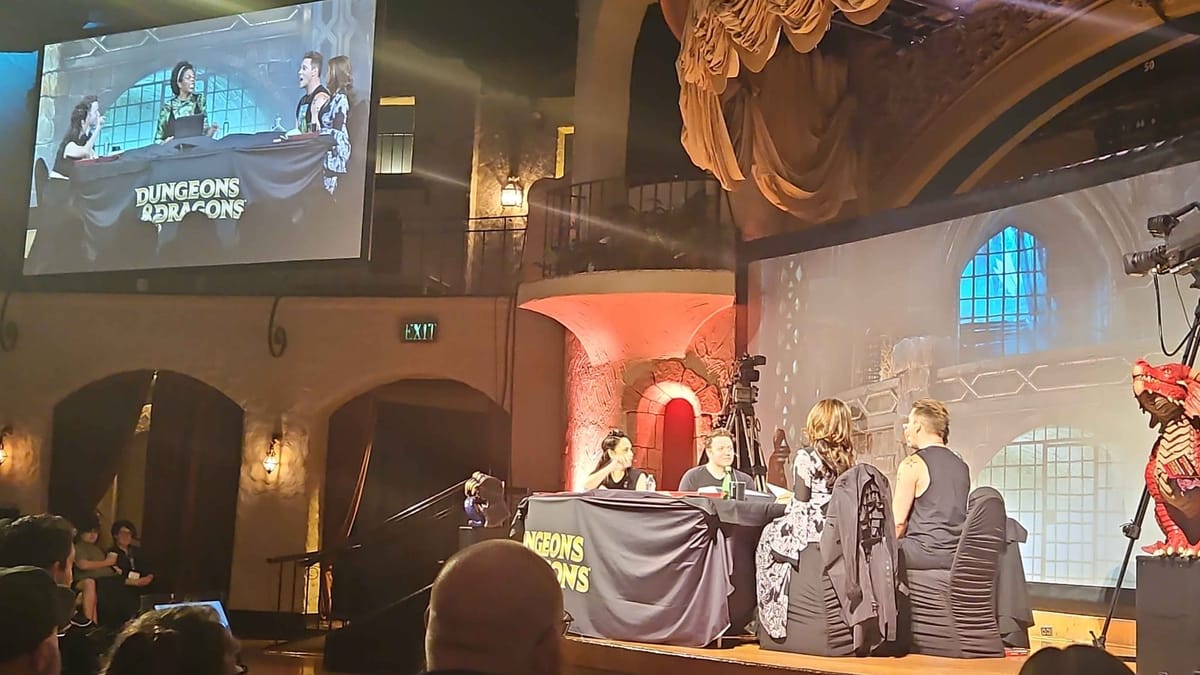

Dungeons & Dragons is celebrating its 50th anniversary at Gen Con with a series of events; some public, some private, and some—like the D&D Live AP in the Indiana Roof Ballroom—kept secret from just about everyone. Two rascals, however, managed to get in through the back door (the main elevator, past the semi-open bar, and through the nearly-full crowd) and found themselves just a few rows away from the action. The action in question included some of the best D&D performers in the world—Aabria Iyengar, Brennan Lee Mulligan, and Anjali Bhimani—alongside two of the most popular D&D actors from Baldur’s Gate 3—Neil Newbon and Samantha Béart (Astarion and Karlach, respectively).

The show started in a place where many D&D games begin—in a tavern. Iyengar, as the DM, started the performance by giving two familiar characters—Astarion and Karlach—a chance to flirt their way through the Chill Touch Tavern puzzle. (The puzzle was just a bartender hoping to steer them down the right path.) Bhimani’s Miri Yannen, a gorgeous but secretive wizard, was hosting auditions for a party to join her on a quest to defeat a dragon that had been killing adventuring parties. Mulligan played Dorbin Kragstone, the cleric of Illmater, the god of “falling down the stairs many times,” who joined up with Astarion and Karlach as they fought their way through Yannen’s trial. After an extended bar brawl complete with a surprising amount of horny jokes and more than a few BG3 references, Yannen joined the party, and the four of them set out to defeat the murderous dragon.

The live actual play was initially catnip for two jaded rascals who cast an eye of skepticism over everything that Wizards of the Coast touches. But, after a positive first impression with the new and improved Player’s Handbook (review to come), we were open to the possibility that D&D might actually be… good? Between Rowan’s respect for the cast’s three actual players and Lin’s well-documented love of Baldur’s Gate 3, the first act of the AP delivered a plate of crow directly into their hands

And then the second act began.

Rowan Zeoli: Okay, I’ll give credit where credit is due. That first act was incredible. Wizards of the Coast has learned how to produce a visually appealing, accessible live AP. There were at least five cameras situated around the room, capturing different angles of the production. In the balcony of the theater, two ASL translators switched off every half hour or so. As far as the performers go, they could not have chosen a better cast. Actual play is a difficult medium to perform live. Compared to scripted mediums like theater, solitary standup acts, or loose group performances like improv, a good live actual play requires a mastery of multiple skills. Grasping the mechanics of a game well enough to be second nature, alongside a compelling collaborative performance, all while setting up and remembering improvised narrative beats to pay off later, is a lot to keep track of. I thought it was a brilliant choice by the casting directors to have three of the most prolific and experienced actual players to support and supplement the two Baldur’s Gate performers with less practice in the medium.

Linda Codega: From the beginning it was clear that Mulligan and Bhimani were there in part to provide handrails for Newbon and Béart. And it worked really well! The two more experienced actual play actors were able to riff off Astarion and Karlach, and the chemistry at the table was really fun to watch. The jokes were landing, like Astarion, the bits were biting, and it was all wrapped up in a classic one-shot fight-and-fetch quest. Having a PC—Bhimani’s Miri Yannen—as the quest-giver was an interesting twist on the standard story, and, again, really helped bring the two BG3 actors up to the level of play and performance expected of a live D&D AP. It’s an incredibly tricky balance and Newbon and Béart absolutely rose to the challenge. Playing fan favorites probably helped too.

Zeoli: Each of the performers were living in familiar territory, which makes sense for a live show. You go to a concert to see the hits. Iyengar as DM always evokes a fun, flirty, chaotic energy from her players. Mulligan played his favorite archetype: a bumbling old man who’s a little bit gross with strong ideological opinions and a collection of idiosyncrasies and missed social cues. Amidst the whirlwind of energy from the other four at the table, Bhimani occupied the role of the straight man, a grounding anchor for the other four players to pull against. In the first act, they clearly established where this story was going, with Kragstone even implying at one point that perhaps Miri Yannen was, in fact, a dragon in disguise. Foreshadowing effectively in an AP is hard to do, but in a comedy-heavy one shot, creating a compelling story between the high joke-per-minute ratio is a masterful act. These are top tier performers; even among the horny chaos, when they decided to command narrative attention, the room went silent.

Codega: As someone who does not watch a lot of Actual Play, and has never seen a live AP show before tonight, the first ninety minutes were an absolute delight. It was incredible to watch these five performers flex their creative muscles on stage. When Rowan says that the room was silent, it’s not an exaggeration. The entire audience was held in rapt attention, hanging onto every word. It wasn’t just fun; it was exciting. I was thrilled to be there.

Zeoli: It’s easy for a live actual play show to get lost in the chaos. Performers can lose command of the audience, but the moment Iyengar’s players decided they wanted to focus on narrative and get serious—that’s what happened. No one questioned them; it was very impressive. When intermission was called, the excited energy in the room was palpable. During that time, the crew replaced each player’s character sheet with a computer, the new Sigil D&D Beyond program set up on-screen. When house lights went back down and the players returned, things were different.

[Sigil is] a product that needs a lot of work before it’s ready to see the light of play.

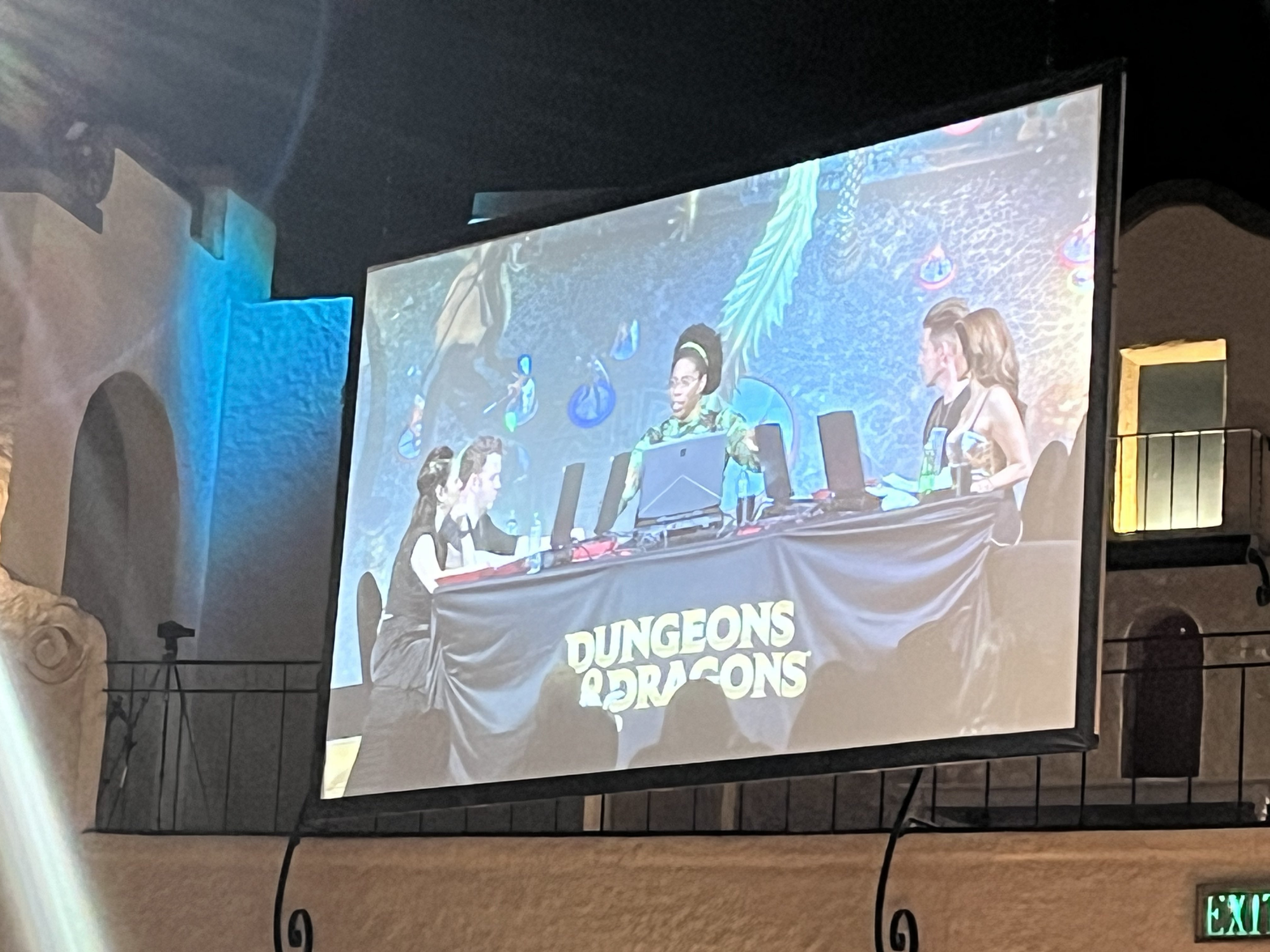

Codega: The moment that the performers started focusing on the screens instead of their scene partners, the air was sucked out of the room. The vibes went rancid. Iyengar explained Sigil, demonstrating some of the features and showing off the graphics… and the minis of Astarion and Karlach that people have seen pop up at other Wizards of the Coast events this weekend. Almost immediately the group entered combat, and it became abundantly clear that not only did the performers not know how to utilize Sigil effectively, but they could barely figure out how to work the basic functions of the program. It was deeply unfair to the actors to force them to use a VTT live that only hurt their ability to perform.

Zeoli: It was a bait-and-switch product demo with performers who did not know, want, or need this technology in order to play D&D for a live audience. Not to say Sigil can’t be used well in actual play. In fact, I could see it being deployed successfully in a number of pre-recorded actual plays, similar to how TaleSpire was used in Dimension 20’s Starstruck Odyssey season, or even live streamed shows where performers know the technology intimately. But this was not that. Lin pointed out during the performance that the players had stopped describing visuals and actions as they did in the first half, taking it out of the theater of the mind and relying on their screens.

Codega: The moment this crystallized for me was when Mulligan’s cleric transformed from a dwarf into a dragon, and, after pressing a button to make the minis change shape, Mulligan immediately moved on. His usual flair for the dramatic, detailed, and specific was lost. The magic of his performance was gone, replaced by a graphic in a computer program. You could practically see the disappointment he felt on stage.

Zeoli: The audience got briefly excited seeing the digital spectacle. But the descriptive elements of play weren’t the only things that were lost to the virtual realm—the players themselves were, as well. Iyengar faded into the background, her job as DM largely subsumed by Sigil. As they gave their performance over to the computer, they also lost the ability to hold the audience’s attention.

Codega: By the time that the combat began in earnest, Iyengar seemed to relinquish a lot of the rules for the sake of getting through the fight as fast as possible. Her responses to questions of distance and attack were “sure” and “why not,” and she seemed eager to allow players to simply choose what was easiest from the list of actions they could manage within Sigil’s apparently baffling interface.

Zeoli: There came a point when it was clear that none of the players at the table wanted to be there anymore. In the beginning and middle of the second act, their split attention between screen and stage meant they could do neither to its full extent. It was clear they could feel the audience slip away from them, due to no fault of their own, and attempted everything in their performer’s toolkit to bring them back. They semi-frantically ran through bits, their body language tense, their words said too quickly, and their volume too loud—all in an attempt to compensate for the weight of the virtual tabletop dragging them down.

Codega: I have to agree with Rowan, even I could see that the actors were struggling through the second act, put in a position where success seemed impossible while they were sharing the table with a half baked VTT. I do feel it is important to be charitable here, simply because the first ninety minutes of this live show was so, so fucking good. Sigil was not ready to be used on this kind of performance, or on stage, and none of the actors were engaged in what was happening, struggling instead to position minis and asking their “unseen servants” to manage their character screens. There was a direct correlation between how much time was spent looking at screens and how little the audience cared.

Zeoli: The most compelling moments of the second act were when the performers pulled themselves away from the virtual and back into the physical. When it was revealed that not only was Mulligan’s character a dragon in disguise, but Bhimani’s character was as well, she stood up from her seat and did a costume change on stage, to raucous applause from the audience. Mulligan, who was largely tuned out when combat occurred on screen, attempted to speed things along. D&D combat is notorious for being a slog, but when Brennan Lee Mulligan has to ask “is her turn over?” there's a real problem. After one final, massive dragon breath attack from the transformed Yannen, Mulligan suggested that the two dragons simply stop fighting. He implied that all of his dragon’s minions had died, despite the fact that their minis had not disappeared on screen, like other downed NPCs had.

Codega: And then… it was basically over, less than 45 minutes into the second act. Without much more fanfare, Iyengar asked if Astarion and Karlach wanted to sneak away while the scorned lovers finished their dragon-sized slap fight. After one final roll on Sigil (and thank God Karlach rolled a 16 on a DC 15 Sneak Check, or else we might still be in the audience) Newbon stood up, asking someone to hum the Pink Panther theme song as he and Béart cheekily walked off stage, ducked across the front row of the audience, and returned to their seats. This act out got the audience laughing as the two actors completely disengaged with the artifice presented at the table, and on screen, allowing their natural chemistry and charisma to work the room one final time.

Zeoli: This was ultimately two different shows. The first, a classic actual play, with more than a little fan service, but with five performers giving their all while the audience (present rascals included) ate it up. The second was an ill-timed, too early ad for a product that needs a lot of work before it’s ready to see the light of play.