Being lucky and playing Steal Away Jordan

It wasn’t "an educational experience".

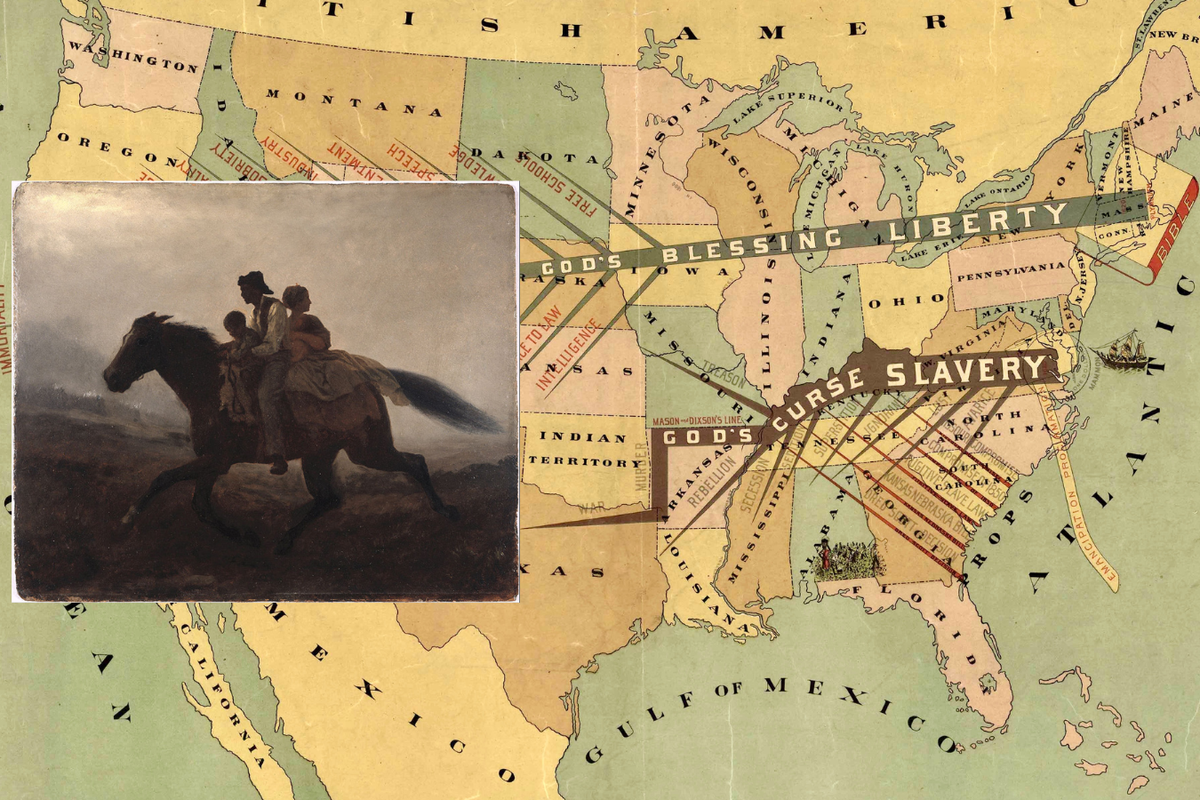

Earlier this year, I played two games by Julia Bond Ellingboe. Steal Away Jordan is a heroic game of African-American slaves, often about them escaping slavery. Tales of the Fisherman’s Wife is a spooky and strangely fuck-y game where you make up stories in the vein of Japanese folk tales. Both of these games are from the “Forge era”—Steal Away Jordan is from 2007, Fisherman’s Wife is from 2012 according to RPG Geek—and they show it in their bespoke mechanical design and scrappy production values.

I’m not sure how I first heard about these games, probably through Evan Torner on social media. He clearly loved these games, and so I was genuinely excited to play Steal Away Jordan. This is easy for me to say, of course. I’m not American, so I approach the game’s heavy subject matter perpendicularly. This isn’t to say that I wasn’t nervous as well. Of course, I was! But I was hopeful that nervousness would be productive.

Steal Away Jordan is a very clever game. Like a lot of Forge games, there’s an energy to its design that feels very familiar. It’s the same energy you sometimes find on itch.io: new designers making stuff unburdened by the norms of tradition—attacking the blank page armed with nothing but a sense of playfulness and possibility. In the game, you don’t make up a name. Instead, the GM names you because that’s how it worked with slaves at that time. The GM also assigns your worth in dice, based on your age, health, and other factors. This pool of dice is what you roll to succeed, so logically, you’d want to make the youngest, strongest, healthiest slave. There’s nothing in the rules to stop you and yet, nobody who is willing to play this game is likely to do that. If anything, by putting a box on your character sheet that says “Worth”, the game slices open the heart of traditional design—it casts the entire practice of quantifying your characters via numbers in a different light. In that same vein, you can divide the whole character sheet into things you decide and things the GM decides about you. The most important elements in your control are your goals and motivations. The GM doesn’t know these at all—they’re just for you and your fellow players, your fellow slaves.

But in some sense, the clever parts of this game are the easiest to notice. They’re in your face. As I played the game, a more subtle part of the design emerged: it’s a game about luck. It doesn’t just use luck—that’s any game with dice. But it’s about luck. This is a game about heroic actions in the face of adversity. The odds are against you and you’re going to have to roll the dice to win. And if you win, it’ll be because you’re lucky. If you’re not lucky, that’s too bad. While we might not like the idea of playing a game where these characters are unlucky, that's only because we know exactly what it entails.